Paper Review: A User's Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System by Stephen Miran

On "Liberation Day", let's hear it from the mind behind the tariffs

Disclaimer: This is not a political post, and in general, this Substack is not meant to be political in nature. My intention is to keep my professional and personal views separate while sharing my understanding of a highly impactful economic policy paper

I am going to put down my thoughts on quite a non-quant paper by Stephen Miran, titled “A User's Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System”, dated November 2024. Paper is available here: https://www.hudsonbaycapital.com/documents/FG/hudsonbay/research/638199_A_Users_Guide_to_Restructuring_the_Global_Trading_System.pdf

Miran was a senior strategist at Hudson Bay Capital as well as an adjunct fellow at the conservative think tank Manhattan Institute when he wrote this paper. He is currently the chair of Council of Economic Advisers, which makes this paper even more relevant. In a nutshell, this paper discusses the rationale behind Trump’s tariffs and gives us an idea about what might come next.

Miran also made some podcast appearances in the recent months, which I found quite interesting. In his older podcast appearances, he spoke more about Treasury issuance, which is a fascinating topic, but it is less relevant to the paper at hand. There is a specific podcast episode which appeared after this paper was written, where Miran elegantly discusses his reasoning and answers some questions. Highly recommend listening to that episode as well, of course after reading this post. Podcast episode is linked below:

Let’s focus on the claims made in Miran’s paper then.

Backdrop

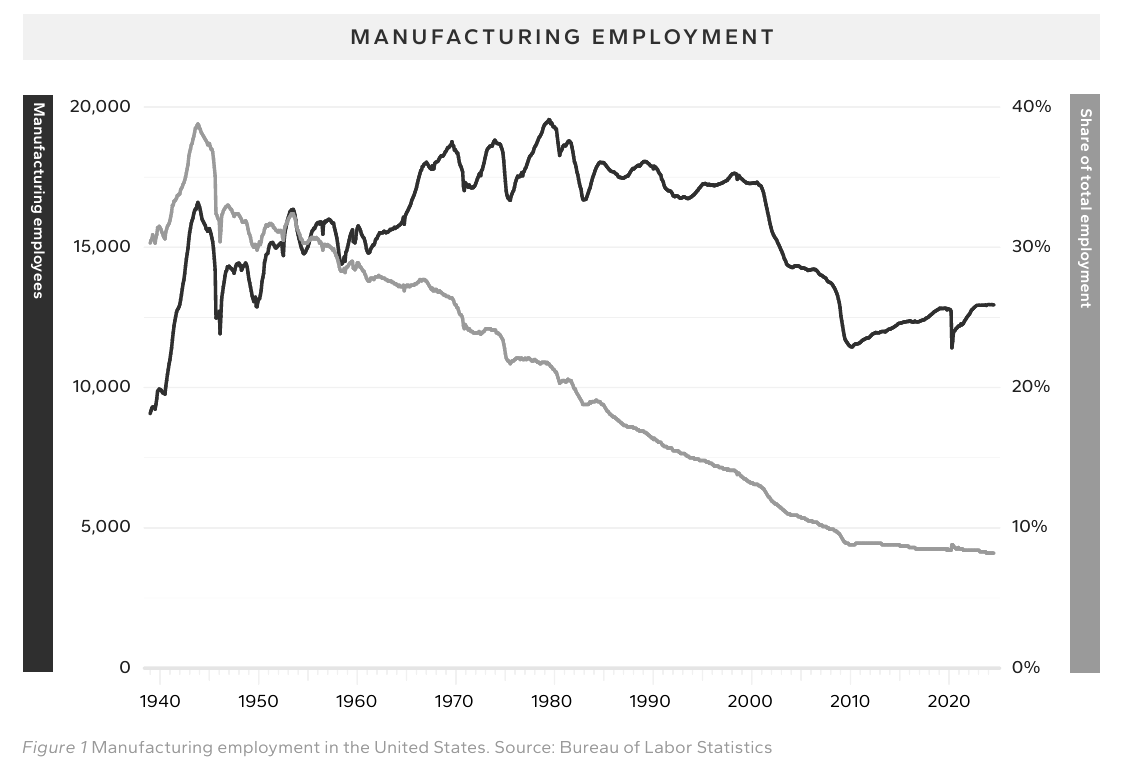

This chart from the paper explains the issue, according to Miran

According to Miran, the global financial backdrop is the following:

US Dollar is the global reserve currency, which results in persistent overvaluation of the dollar

Strong dollar causes US exports to be expensive (i.e. less competitive), weakening the US manufacturing sector while the US consumer enjoys cheap imports

US trade partners such as China hold on to USD reserves, keeping their currency weak. This results in ex-US GDP to increase, and US GDP to be a smaller portion of the world GDP

Weak(ening) US manufacturing causes US trade deficits to widen

Normally, wider trade deficits would mean less demand for local currency (USD in our case), allowing the currency to weaken. This doesn’t happen for the USD, due to item 1, USD being the global reserve currency

With the rest of the world GDP increasing, demand for US assets also increase, resulting in even larger debt issuance and trade deficits by the US

Item 5 is the lynchpin for the US dilemma, and the key in Miran’s arguments. He argues that in a “Triffin world”, named after Belgian economist Robert Triffin, it is not the trade relationships that determine the currency strength for a reserve currency. Rather, the reserve currency is a form of global money supply, and the supply/demand for the reserve currency globally is what determines the currency strength.

In the Triffin world, reserve asset producer exports the reserve currency (dollars) by borrowing cheaply, and it fuels the rest of the global system. US borrows cheaply because there is price inelasticity for the demand. No matter how low the US treasuries yield (i.e. how expensive the bonds are), there is always demand for the reserve currency. Even in instances when one would expect the bonds to cheapen, such as the almost-default of the US and the credit downgrade, US treasuries rallied, not sold off. If any other country openly debated defaulting on their debt, the yields of that country’s bonds would have skyrocketed. Not for the US.

This all works well until the reserve asset country accumulates debt that is so large that servicing this debt becomes a problem, resulting in credit risks increasing. This would create a breaking point in the Triffin world, called the “Triffin dilemma”: eventually the reserve currency has to weaken after trade deficits balloon and debts increase to unsustainable levels.

Miran’s Prescription

Miran suggests tariffs to be the first step in his prescription to reshape the global system.

Tariffs

He claims that tariffs won’t be inflationary, since the USD will appreciate by the same amount. Assuming a Chinese widget maker keeps selling their widgets at the same price in Chinese Yuan; if the Dollar appreciates by the same amount as the tariffs, these two effects would net each other and there won’t be an inflationary effect for the US consumer. In the meantime, US government would be collecting tariffs, which can be thought of as a tax for financing the global financial system.

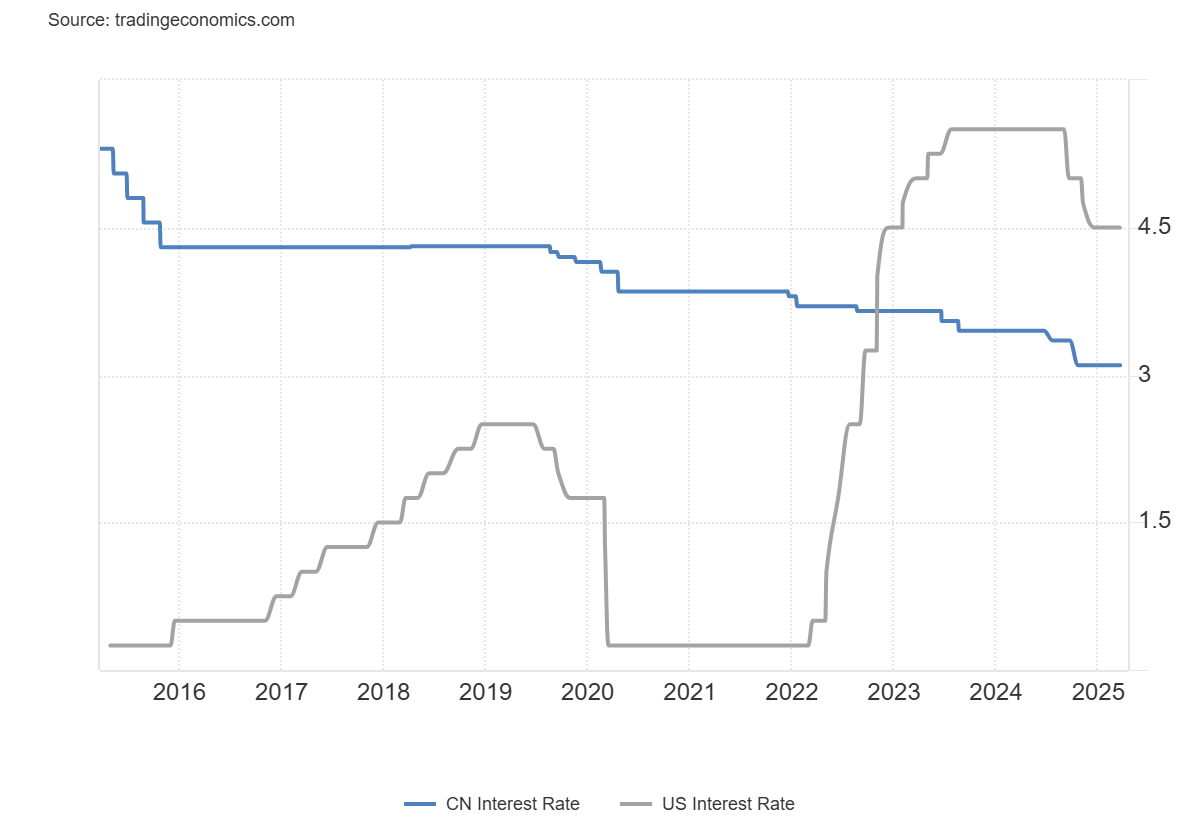

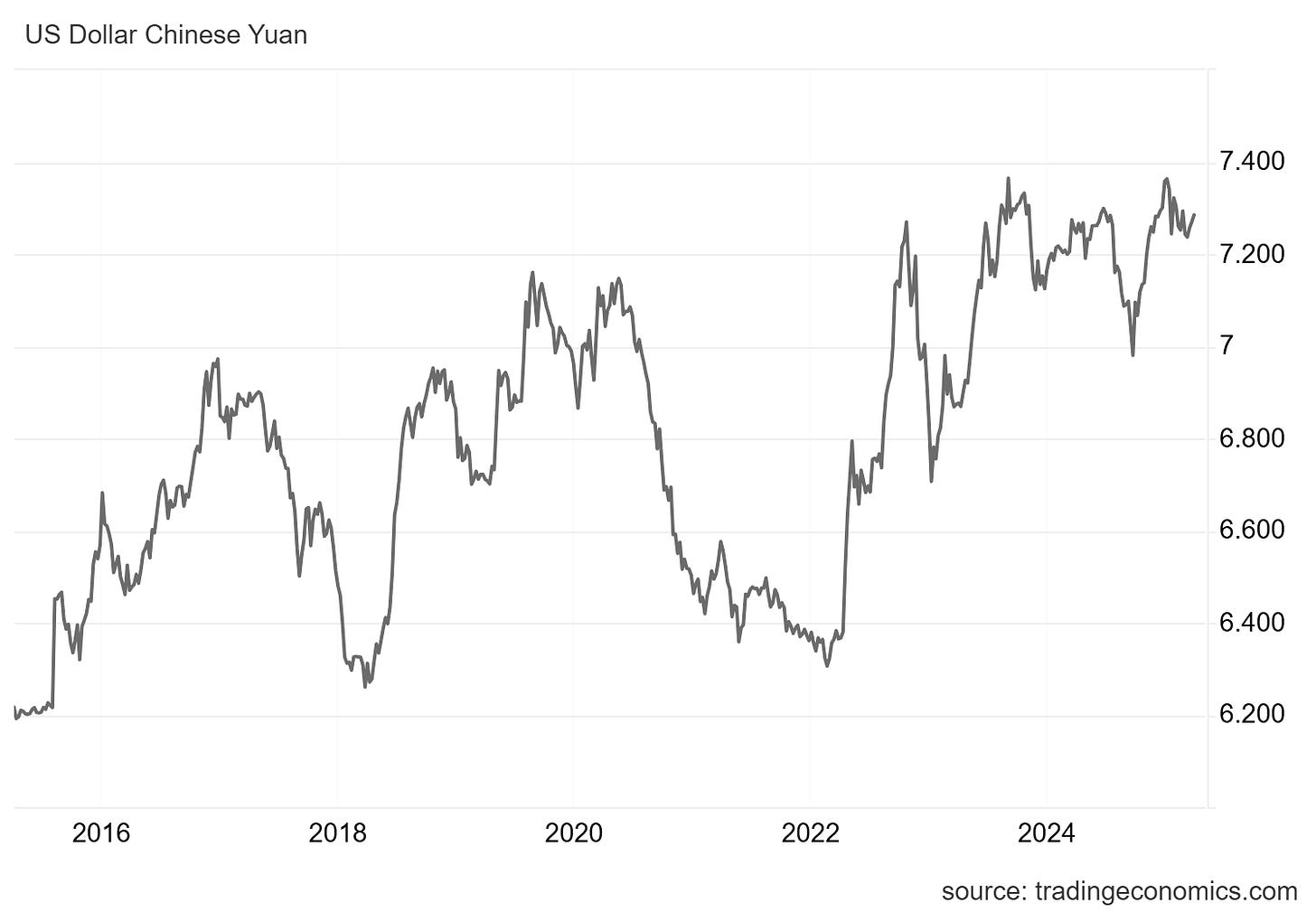

In order to back his very bold claim that the USD will appreciate as tariffs go into effect, Miran gives the 2018-19 tariff example. USD indeed appreciated during that time period, neutralizing some of the impact of tariffs. This is not something we can always rely on though: during that same time period, Fed was raising rates while Bank of China stayed steady. Appreciation of USD against CNY was much more likely due to the central bank action than the trade effects of tariffs. By the very own admission of Miran, trade relationships are less impactful on the value of a reserve currency than the supply/demand for reserve assets.

In other words, I think Miran’s argument that burden of tariffs will not be borne by the consumers is incorrect. This relies heavily on a false assumption that USD will get stronger, and this is not a done deal. To give him credit though, he does consider the possibility that there is no currency offset, and concedes that tariffs would be inflationary in this scenario.

Note the increase in USD/CNY (i.e. USD getting stronger) during the same 2018-2019 period that Miran talks about in his paper.

The second inconsistency I find in Miran’s argument is that stronger USD will result in US manufacturing sector becoming even less competitive. So, either tariffs will be inflationary, and the consumers will be hurt; or tariffs will not be inflationary, and the manufacturers will get hurt. Miran seems to argue that manufacturing sector will flourish as a result of tariffs, and consumers will not be hurt due to USD appreciation. This seems like a contradiction.

Security Guarantees

Miran goes on the tie tariffs to security guarantees, by saying that the US should impose tariffs on nations not only based on the size of their trade deficit and existing tariffs imposed by the foreign nations; but also based on security guarantees.

To be honest, this is where things might be going next. The only stop to an escalating trade war is for the US to pound the table and tell the EU and other trading partners that the US defense guarantees are on the table, if they wanted to retaliate the tariffs. This creates a very transactional world, in which the tariffs can be traded for a security umbrella at the expense of the global trust in the US, and eventually the reserve currency of the dollar.

Currency Adjustments

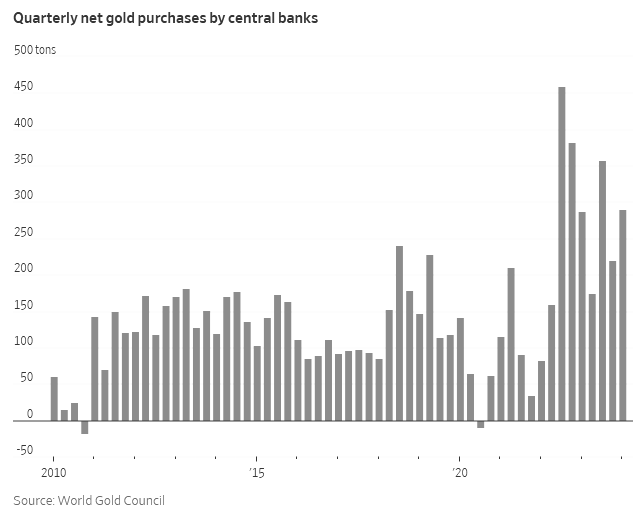

Using security guarantees as a trade-off for tariffs is a is a risky move, which could result in the de-dollarization of global trade. This has already been happening in a small but meaningful scale, with the increase of gold purchases by central banks. Consider this WSJ article from 2024: https://www.wsj.com/finance/commodities-futures/golds-latest-allure-its-sanctions-proof-4c3cc4f3

From the WSJ article: “China’s central bank, in particular, has been buying gold for 18 straight months since November 2022, boosting its gold reserves by 16%, or 10 million troy ounces.”

To Miran’s benefit, he also admits that any policy that would weaken the dollar would make US assets less attractive for global investors, and that such policies have not been tried at scale. He suggests using Fed policy would be one way to implement a broad currency valuation framework and goes further that Fed might even hike rates to counter the inflationary effects of a weaker USD and therefore higher imported inflation. Of course, what is very unclear here is that the author was suggesting that tariffs won’t be inflationary at all due to the currency offset (USD getting stronger), and now we are back to talking about what Fed might do when the USD gets weaker and we import inflation due to tariffs.

Mar-a-Lago Accord

Miran’s final and boldest suggestion is to create a Plaza accord-like structure where the US works out a deal with closest trade partners that involve tariffs, USD reserve status, US borrowing costs as well as security guarantess. This would involve:

US trade partners to keep USD cheap, in order to give an edge to the US manufacturing

US trade partners to buy US treasuries, so the US can continue to borrow cheap and maintain reserve currency status

US would relax tariffs on such trade partners, and

US would provide security guarantees in the form of NATO and regional commitments

This accord is only feasible is the partners have USD reserves to sell in order to make the USD cheaper. This would require the participation of Middle Eastern (OPEC) and Asian countries in the accord. Rest of the developed world such as Canada, EU and Australia would not be enough, since they collectively do not have the power to cheapen USD.

Conclusion

I think it is worth spending the time and reading this paper yourself, while keeping my comments in mind. I am especially surprised by the obvious inconsistencies in the tariff argument by Miran. Given the tough times market participants are experiencing in the wake of the “liberation day”, I think one thing is certain: uncertainty.