In this post, I share my understanding of what might have caused some of the dislocations in the bond (and currency) markets, which could have been a contributing factor in the reversal tariffs, at least temporarily.

Backdrop

It feels like months have passed since I wrote about the paper which seems to be the intellectual underpinnings of the trade war, which you can read about here, even though it has only been less than two weeks. In the meantime, we’ve seen a massive sell-off in the equity markets, which was somewhat reversed after Trump announced a 90-day moratorium on most tariffs.

I believe the important question in many investors’ minds was what caused the Trump administration to walk back the very oddly calculated tariffs. As a recap, initially announced tariffs were calculated by assuming that the US trade deficit with a given country as a percentage of imports was purely driven by tariffs, and imposing half of that quantity as the tariff measure. For countries with less than 10% trade deficit (or even surplus, if one existed) a convenient 10% tariff floor was applied. Financial Times has a nice chart showing the now reverse-engineered relationship, key chart is produced below.

Since the proposed tariffs were significantly larger than the markets initially anticipated, a very large stock sell off ensued.

Live chart: https://www.tradingview.com/x/Gao2Txi1/

Many investors were hurt, but to me the biggest information content of this episode was not how it started but rather how it ended faded. Trump walked back most of the tariffs on April 9, which seemed to be in response to the market reaction. The question is, which market? While it is impossible to know for sure, the commonly agreed answer seems to be the bond market. In fact, it seems like we came very close to a malfunction in the bonds market and the Fed stepping in.

On April 11, Mohamed El-Arian put the issue very elegantly:

https://x.com/elerianm/status/1909946674769715609

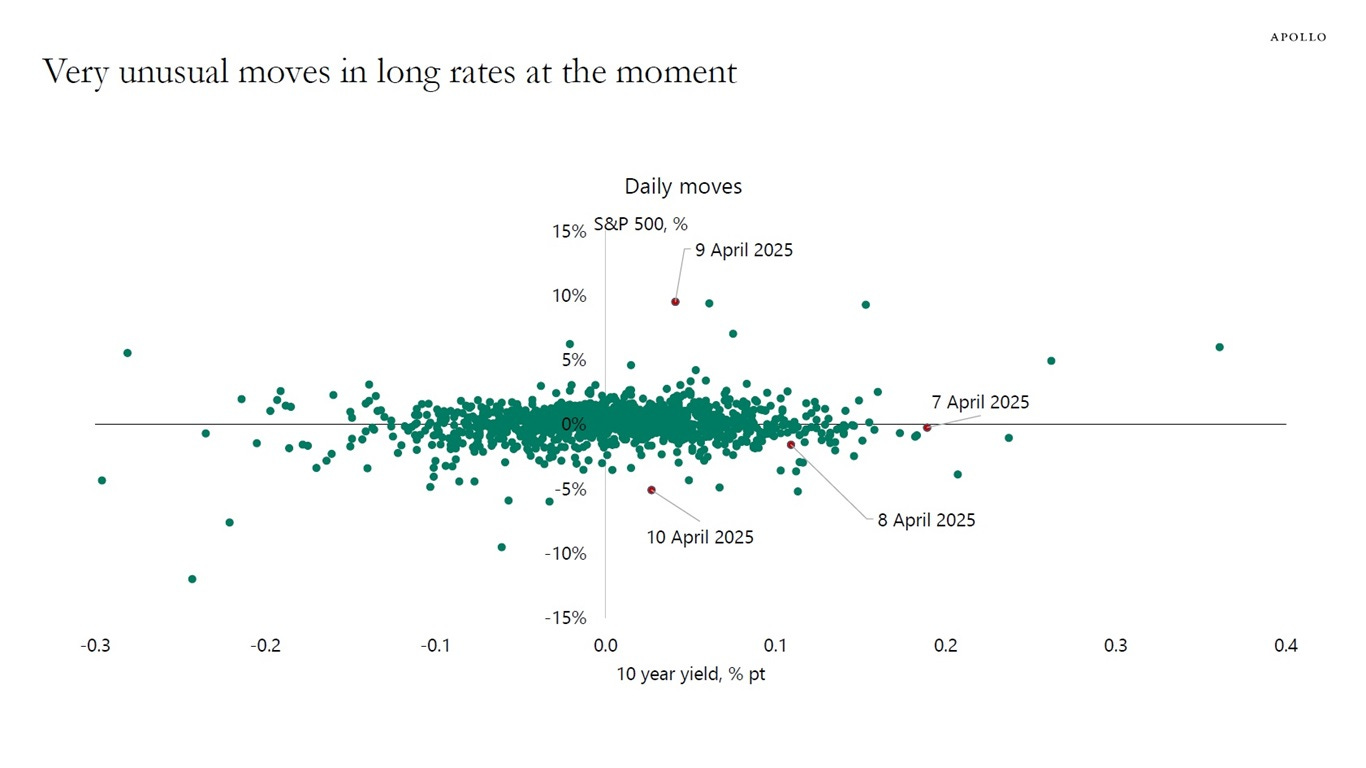

Indeed, these moves were so beyond the pale that Torsten Sløk also picked up on the unusually uncorrelated moves in US 10yr yields and S&P500, and offered a few possible explanations.

From Apollo Academy: Why Are US Long-Term Interest Rates Moving Higher?

Slok postulated that the moves could be due to a combination of (1) foreigners selling US Treasuries, (2) investors derisking all assets and moving to cash, or (3) unwinding of the basis trade. I agree with his view on all accounts. The moves are highly unusual in the sense that Treasuries kept selling off as stocks posted losses and later on gains.

Especially the move on April 7 is eye opening. On that day, US yields went up 20bps, despite a rather muted day on the stock market. As Slok puts it in a separate blog post, this was most likely due to the unwind of the basis trade. Unwind could be considered a technical term for blow up.

What is the Basis Trade?

In a nutshell, basis trade involves going short the Treasury futures, and going long the Treasuries.

There are a few forces that make the basis trade possible:

In the post-GFC world banks have higher capital requirements, resulting in large quantities of Treasuries that sit on the bank balance sheet

On the other hand, many long-only asset managers such as mutual funds, pension funds and even insurance firms are long term buyers of treasury futures, since futures are a capital efficient way of gaining exposure to the bond market

During normal times, demand for treasury futures is higher than that of cash treasuries. This creates an arbitrage opportunity, since these two markets are linked through the CTD (Cheapest to Deliver) mechanism. Bond futures are “deliverable”, meaning that if an investor holds the long bond future to maturity, they get the delivery of the cash bond that is cheapest to deliver. Due to demand differences, treasury futures are slightly more expensive (yields less) than cash treasuries

Hedge funds that want to capitalize on this arb opportunity would structure the trade as follows:

Borrow the US Treasury from a bank on the repo market (i.e. pay the repo rate), and create a long bond position

Short the US Treasury Futures on the futures exchange

This trade usually chugs along until there is a liquidity crisis. When the banks need to increase their capital levels and call back the treasuries they are lending out, they do so by increasing the repo rates they charge to lend out the treasuries. Higher borrowing costs mean the trade becomes highly unprofitable, therefore hedge funds book losses and close the basis trades.

For an excellent treatment of how the basis trade is structured and sources of its returns, one should read the covid-era paper written by the highly respected folks at the US Treasury department’s Office of Financial Research:

OFR Brief Series: Basis Trades and Treasury Market Illiquidity (I will probably write a paper review post on this at some point)

Aftermath of April 7

It is only a week after the April 7 bloodbath, so we do not have the full picture in terms of hedge fund returns. We have started getting some indication that basis traders at pod shops started getting the tap on the shoulder by the risk folks, based on reporting by Bloomberg (here and here).

Getting Tariffed

Referring back to my review of the Stephen Miran’s paper, “A User's Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System”, the author mentioned that tariffs could revive the US manufacturing sector while reducing trade deficits, as long as the following were true:

US Dollar remains the reserve currency of the world

US Treasury demand remains strong, resulting in lower yields

As I mentioned in my analysis of that paper, I think the paper is has some contradictions. We do not know exactly what caused the sell-off in the bond market, but given the beta neutral nature of the basis trade, I doubt the casualties in the basis trading community was the cause of the bond sell-off. Sell-off was more likely to be caused by panic selling by the global investors, in anticipation of de-dollarization by the global players as a tariff response.

This also makes sense within the framework of Miran’s paper: he told us that the main export of the US was dollars, since it is the reserve currency of the world. When the US tells the world it is not willing to buy the global goods, rest of the world tells the US that it is not going to buy the number one commodity US is selling back to the world: the US Dollar, and the Treasuries.

We are going through precarious times. Basis trade does not make it easier, and it is a dangerous, highly levered trade that can blow up at any point. Since Fed did not step in size this time, I do not think we’ve seen the worst of it yet. What Trump does going forward with respect to tariffs will likely guide how the bond market reacts.

Being the global reserve currency brings immense advantages: lower borrowing costs, persistent demand for sovereign debt, and unparalleled financial influence. But reserve status is not a birthright. It comes with stringent, often overlooked requirements. Chief among them: the currency must be anchored to a safe haven asset; one that is universally trusted, highly liquid, and fundamentally risk-free. In a world where the safety-liquidity-return hierarchy governs global capital flows, breaching the “safety” pillar would be the most dangerous move of all.